"You always assume we must have fallen, that we were thrown out of heaven. Some of us just jumped."

- Bertrand

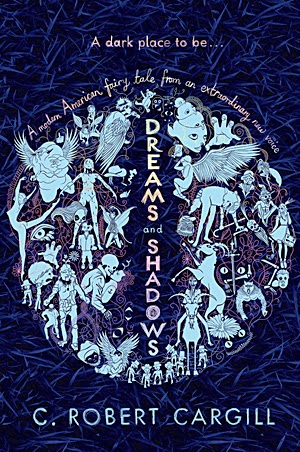

So I went with my gut, and turned it aside. I read other things. I tried time and again to batter through the literary Great Wall that is Gravity's Rainbow. I read an interesting biography of National Lampoon. But finally, when I saw a sequel had come out to Dreams and Shadows, and said sequel was on the shelf at the local library, and it seemed like it was actually a series worth reading. "Okay," said I, "We'll give this Cargill guy a proper shot, then." And while I could not get Queen of the Dark Things because the new books section at my libraries exist solely to taunt me with the option of books I cannot check out due to living so impossibly far away from the libraries that even if I were allowed I could not check them out, they did have a copy of Dreams and Shadows. I'd done it. I'd decided to go against my gut in the service of possibly picking up something that was at least in part still part of the zeitgeist.

My lesson for you today is this: DO NOT trust your fucking gut. Because your gut is good, but when you have nothing to risk but time and another book you have to read because it's due back to the library, you can't afford not to take a chance on a book. And while you may be dragged through your Catherynne M. Valentes, your Max Freis, your Lev Grossmans and the like, there's a chance you're passing up a heartbreaking work, a work that could damn well be a favorite. Read everything and discard the stuff you didn't like as much, because that's how your taste stays killer. But never tell yourself "I won't like this book", because screw you, you have no freaking clue whether you'll like it or not until you try. Experimentation. Discovery. Risk. It's what makes life fun.

And Dreams and Shadows is the perfect argument for why not to do this. It's a beautiful book, packed full of characters and setting and interesting dialogue and some odd interludes about anthropology and existentialism. While you may not enjoy it as much as I did, C. Robert Cargill's first novel is a book that does not simply grab your attention, but then shakes it back and forth while shouting at it. I need to buy this. I'm surprised I haven't yet.

Dreams and Shadows by C. Robert Cargill is a story about stories. Sort of. Bear with me, here, folks.

Dreams and Shadows is, at its core, a book about two young men: Ewan Thatcher, a human child made into a changeling fey; and Colby Stevens, a little boy who decides to make an innocent wish to "see the world, and everything in it". Colby makes this wish because a genie named Yashar appears in the woods. Yashar is a djinn forced to wander the earth without rest, and sustains himself on granting the wishes of little children. While Colby at first is told to wish for something small, something an eight year old would want, he is far too inquisitive and asks Yashar questions about where he comes from and what's all around him. This leads to Colby making a wish, a wish he thinks is perfectly innocent. After trying to dissuade him with the knowledge that he doesn't quite know the consequences his action will have, Yashar grudgingly grants Colby's wish and starts off on their grand journey to see the world and everything in it.

Their first stop is Fairyland, where while Yashar talks with the council about the wish Colby made (a wish which seems to have implications elsewhere), Colby meets a young boy named Ewan. Ewan is mostly human-- mostly because he's been raised as one of the fey-- and around Colby's age, so the two (who first argue over the limited knowledge of the other's world) become fast friends and spend their time playing in the fields with a Sidhe named Mallaidh, Ewan's childhood sweetheart. However, all is not bright, as they are watched by a malicious nixie called Knocks, the same nixie who took Ewan's place in the human world as a changeling and drove his mother to an early grave. However, Knocks's machinations are interrupted when Hell's own Wild Hunt interrupts things by dragging several fairies off to Hell at the behest of Ewan's dead mother, Tiffany Thatcher, who has since become mistress of the Hunt.

Colby and Yashar are forced to leave, but not before Colby hears his friend is to be sacrificed as a "tithe child" to Hell in place of an existing fairy. This spurs him to sacrifice his innocence to make a second wish, a wish with even further untold consequences: He forces Yashar to make him a wizard of indeterminate power, and then storms the sacrifice ceremony, destroys Schafer, one of the dark fey representatives on the council, and takes Ewan forever from the land of the fey in return for not vaporizing more of them.

And if it ended right there, then that would be it. A tale of innocence lost and evil fairies, featuring cameos from Coyote and massive carnivorous goats from Hell is a good story in and of itself. But it goes on.

Years later, Colby is a wreck, a man who knows way too much too soon, working in an occult bookstore in Austin and drinking at a bar for the cursed and damned with his best pal Yashar. Ewan, also in Austin, is a musician whose band, the Limestone Kingdom, is destined for mediocrity. But while Colby might be finished with the past, and Ewan might have forgotten it all as some odd dream, the past isn't exactly through with them. Coyote resurfaces, planning something in which Colby and Ewan both play a part. Knocks and his malicious gang of Red Caps (fey who are addicted to bloodshed and smear their caps with the blood of their kills) have descended upon Austin to feed on its inhabitants...only to notice that Ewan still lives there. None of these people can escape their destinies. But with a little luck, they might be able to make things easier and just maybe, maybe they'll be okay.

Okay, first things first, I have to praise this book for its awareness of the genre. Dreams and Shadows is very aware of its place and what it's doing, and that's actually rare for books that enter the "literary" canon. It takes the tropes of fantasy-- wizardry, coming of age-- and turns them inside out while still keeping them intact. It's quite a feat of acrobatics, and one reminiscent of Neil Gaiman before he got big. In fact, with a few prods and tweaks, the first half of the book could very well be something like a very dark children's book-- the story of Colby the Boy Wizard and his Friend Yashar the Genie. It doesn't turn out that way, but this isn't as happy a book as those usually were. The second half easily and effortlessly succeeds where Lev Grossman failed utterly and fell on his face, showing the real-life consequences of growing up in a world full of magic, and especially one where your best friend does not and cannot know that he's secretly a former fey sacrifice. While Colby has the reputation as a powerful wizard who successfully cowed the fey, he hates the reputation and that he has his own story that matches the stories of his friends like Yashar and his enemies like Coyote. Among the other things he has to deal with on a daily basis, like demons and angry fey.

And that's the thing at the center of this that I like. The book isn't so much about the characters, or the plot, or anything like that-- it's about the stories. And Cargill uses the stories in Dreams and Shadows to accent the plot and add more to the setting. Stories are important in Dreams and Shadows. They provide background into the characters' true nature, offer a deeper view of the world everyone lives in, and inform the way things eventually turn out. It says something that at the end, the characters play out their own stories-- star-crossed lovers, trickster gods, tragically cursed, boogeymen, et cetera-- to their inevitable conclusion and then become legends themselves. To further drive this point home, chapters are occasionally intercut with selections from anthropology books about the very creatures the characters interact with, allowing more stories to seep into the plot. It provides a nice counterpoint to everything.

But the characters are fantastic. You want these people to stay. You want them to feel some bright spot of optimism in their lives. And it's heartbreaking how they keep struggling as the odds continue to mount in places. My personal favorite is Bertrand, a fallen angel who left God's presence willingly, or as he put it, "jumped". He's such a tragic figure, but somehow despite the tragic cynicism, manages to be optimistic. It says something that even the secondary characters, even something that could be so cliche and used as an existential mouthpiece about the nature of God offers up a decent and well-rounded person. They're sympathetic for the most part, too. I even rooted for the Wild Hunt at points, and it's a rare talent that makes the monstrous legions of Hell sympathetic. The one character that doesn't seem at all sympathetic is Knocks, though there are reasons for this.

Those reasons tie into the plot, and the thing I like about the plot is that it unfolds. I've tried to do my best to conceal part of it, though I had to spoil some of it to give you the basic plot structure. At first, I thought it kind of meandered a little, as it spends a lot of time setting up the setting and characters and various threads and stories to follow. But Cargill treats each individual story like a single domino in part of a set, and it's the set that's really the important thing. While the plot will just introduce characters and settings and go into peoples' lives, and this is great, it's that there really is a purpose tying the whole thing together that really makes this work.

Unfortunately, this is where the issues come in, and they come in in force. Knocks is a rare two-dimensional villain in a book filled with three-dimensional characters. In fact, the villains seem a little too mustache-twirling at times, a little too secure when everyone else isn't. And there are moments where things happen in the plot that perhaps feel like it's the plotting of convenience rather than organic plotting. And there are moments where the plot basically says "this is the way it's supposed to be, I can't give you what you want", and it seems...arbitrary. Like Cargill's just yanking the rug out from under everyone for kicks. Like he wants the plot to do something, and so no matter where things need to go, it's going to do that thing. It's a kind of inexperienced way of going about it.

But...there is a reason. It's a story. It's a story being manipulated by a master storyteller. In-universe, even. And that master storyteller gives a lot of these things a pass, especially because he's kind of an asshole. It's a similar premise at a certain point to the masterful Fool on the Hill. If the ultimate "bad guy" was more interested in proving a point than telling a story. And...when the final plot twists are revealed and everyone sees exactly what was wrought...it works. Not well, and it jerked me around, which I don't normally like unless you're Mark Z. Danielewski, but it works.

And in the end, that's what matters. The book works. It's sad, it's beautiful, it's melancholy, and for a first novel, it's damned amazing. Get your hands on this any way you can. Make a space for it in your head. It's worth your attention, even if you don't dig it, and hopefully this is the signal for more to come from Cargill and his imagination.

And always remember: If something is too good, it probably isn't good at all.

NEXT WEEK:

Death Warmed Over by Kevin J. Anderson

AND MANY OTHERS

*Folks, it is very simple. When people stop recommending this book to me, I will stop hanging it from the rafters of a dingy warehouse and using it as a punching bag. It is actively malignant, and from what I've read of the sequels, so are they.

** The Night Circus, an inverse of the problem of The Magicians, is a beautiful book written a lot worse than the plot actually deserves. But we'll get to that another day.

No comments:

Post a Comment